From Washington’s modest oath to the twenty-first-century “imperial presidency,” the trajectory of American executive power traces the history of the republic itself, its fears, ambitions, and evolving sense of governance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

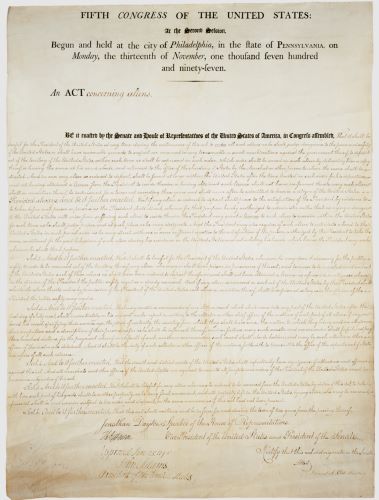

From the moment the Constitution was signed in 1787, Americans have wrestled with the paradox of power in a republic built on restraint. The framers feared monarchy but also distrusted weakness. They sought a national executive strong enough to govern effectively yet constrained enough to prevent tyranny. Article II of the Constitution outlined a presidency that could command the armed forces, execute the laws, and conduct foreign affairs, but it left much of its scope undefined. This ambiguity, part philosophical, part practical, has proven the most elastic clause in American governance. Over more than two centuries, through war, industrialization, crisis, and global expansion, that ambiguity has stretched into a vast and evolving conception of executive authority that few framers could have foreseen.

The presidency began as a modest office, largely reactive and bounded by legislative supremacy. In the early republic, presidents like George Washington and John Adams deferred to Congress in most domestic matters, setting precedents of self-restraint. Yet within a generation, Thomas Jefferson’s unilateral purchase of Louisiana hinted at how executive initiative could alter the very map of the nation without constitutional amendment. The slow accretion of such precedents (each justified as necessity, prudence, or national interest) became the architecture of what scholars later called “the living presidency.”1

The nineteenth century transformed this architecture through war and expansion. Andrew Jackson redefined the office as a populist engine of political will, and Abraham Lincoln, faced with civil war, claimed powers of emergency that permanently altered expectations of executive leadership.2 The twentieth century accelerated that trajectory beyond recognition. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the mobilization for World War II created an administrative apparatus that turned the presidency into the nerve center of a modern state.3 By midcentury, the balance of power envisioned in Philadelphia had tilted decisively toward the executive branch, a shift captured in Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s description of “the imperial presidency.”4

The postwar and Cold War presidencies entrenched this dominance under the banner of national security. Subsequent decades, from Richard Nixon’s assertion of secrecy to George W. Bush’s wartime authorizations and Donald Trump’s expansive view of unitary authority, reveal a continuous line of evolution, not aberration.5 The presidency has become both the symbol and the engine of American political identity, expected to lead, act, and decide swiftly in a world that rarely pauses for deliberation. What was once a single constitutional office has become a sprawling institution encompassing intelligence networks, regulatory agencies, and global command structures.

What follows examines that long evolution from the founding to the present day. It argues that the growth of executive power has been neither accidental nor purely constitutional but structural, rooted in the nation’s recurring crises, its global ambitions, and the political culture that prizes decisive leadership. Through successive epochs (the Founding, the nineteenth century, the Progressive and New Deal reforms, the Cold War, and the post-9/11 era) the presidency has continually expanded its reach by blending formal authority with informal influence. The result is a modern executive whose power, once constrained by checks and balances, now defines the tempo of American governance itself.

The Founding Era and the Limited Presidency

Constitutional Foundations

The Constitution’s framers approached executive power with deep ambivalence. Having just cast off a monarchy, they sought to create an executive energetic enough to enforce law but restrained enough to avoid despotism. Article II reflects that tension in its brevity and ambiguity: it vests “the executive Power” in the president, grants specific authorities (command of the armed forces, veto power, treaty negotiation, appointments) but provides little elaboration on their limits. The debates in Philadelphia and in the Federalist Papers reveal that this vagueness was deliberate, allowing flexibility while depending on political norms and virtue to prevent abuse.6 Alexander Hamilton, defending the new Constitution, argued in Federalist No. 70 that “energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government,” yet he also emphasized that accountability required unity and public scrutiny.7

George Washington’s presidency became the crucible in which those principles were tested. His careful deference to Congress and insistence on executive neutrality set precedents for a limited and dignified office. He refused monarchical titles, sought Senate consent for treaties, and declined a third term to affirm that executive power was service, not dominion.8 John Adams inherited that ethos but quickly confronted its fragility when partisan division led Congress to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. Although Adams enforced them cautiously, their very existence alarmed critics like Thomas Jefferson, who viewed them as evidence of creeping authoritarianism.9 The first transfer of power in 1801, peaceful and constitutional, was thus not only political but philosophical, a reassertion that executive authority must remain subordinate to republican consent.

Early Expansion and Ambiguous Precedents

Yet even Jefferson, champion of limited government, soon expanded presidential authority beyond clear constitutional sanction. His authorization of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the nation’s size and did so without explicit congressional or constitutional approval. Jefferson justified his action on pragmatic grounds, claiming necessity for national security and prosperity. This act inaugurated a pattern that would recur across centuries: presidential initiative creating new constitutional interpretations that Congress and the courts would later absorb as precedent.10

Subsequent administrations navigated similar tensions. James Madison, though architect of checks and balances, asserted military authority during the War of 1812 that strained those same principles. Andrew Jackson went further, transforming the presidency into a direct instrument of popular will. His defiance of the Supreme Court in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) and broad use of the veto expanded the president’s power to act as an independent political force rather than merely as executor of legislative will.11 By mid-century, the United States had witnessed both the potential and peril of executive initiative: an office designed for balance had become increasingly capable of unilateral action when circumstances or personality demanded it.

The founding generation could not have foreseen the scale of future government, yet the ambiguities they left behind ensured that later presidents would find ample room to redefine their powers. The “executive Power” clause, the “take care” obligation, and the commander-in-chief designation became living texts whose interpretation evolved with every emergency, war, or crisis. From these origins, the seeds of modern presidential authority were planted in the very soil of constitutional compromise.

The Nineteenth Century: War, Expansion, and Gradual Shifts

War Powers and Foreign Policy Expansion

As the young republic expanded westward, so too did the practical reach of presidential authority. Although the Constitution vests in Congress the power to declare war, nineteenth-century presidents repeatedly used military force without formal declarations, establishing a precedent of executive initiative in foreign and military affairs. Thomas Jefferson’s deployment of naval forces against the Barbary States in 1801, undertaken without explicit congressional authorization, signaled the emergence of a flexible interpretation of commander-in-chief power.12 His successors followed suit. James K. Polk’s conduct of the Mexican-American War (1846–48) pushed those boundaries further still. Polk justified his decision to send troops into disputed territory by claiming the United States had been attacked, a formulation that effectively allowed the executive to determine the existence of war.13

The expansion of territorial and military power coincided with a widening of executive diplomacy. Presidents negotiated treaties, recognized new governments, and established informal spheres of influence with minimal legislative interference. In these acts, the presidency acquired the character of national agent abroad and political leader at home, a dual role that would later become the essence of modern presidential identity. Yet each assertion of autonomy in foreign affairs carried constitutional tension. Critics like Senator John C. Calhoun warned that “executive wars” threatened to erode the legislative check that had once protected the republic from monarchical tendencies.14

Institutional and Administrative Evolution

Domestically, the nineteenth century was less about legal redefinition than about political transformation. Andrew Jackson’s presidency marked a decisive break from the deferential model of the founders. Jackson claimed to embody the direct voice of the people and wielded the veto as a positive political weapon, not merely a constitutional safeguard. Between 1829 and 1837, he issued twelve vetoes, more than all his predecessors combined, establishing the president as the center of national policy rather than a passive executor of congressional will.15 His fight against the Second Bank of the United States demonstrated the presidency’s new capacity to shape economic policy through moral appeal and public mobilization.

The Civil War amplified these tendencies to an unprecedented degree. Faced with rebellion, Abraham Lincoln exercised powers that stretched the Constitution’s text nearly to its breaking point. He suspended habeas corpus, expanded the army and navy without prior congressional approval, and issued the Emancipation Proclamation under his war powers as commander-in-chief. Lincoln justified these actions as necessities to preserve the Union, insisting that extraordinary crises required extraordinary measures.16 The Supreme Court’s later decision in Ex parte Merryman (1861), which questioned the legality of unilateral suspension of habeas corpus, went largely unenforced, demonstrating how practical necessity could eclipse legal formality when the executive acted decisively.17

After the war, Reconstruction brought a temporary effort by Congress to reassert control. The Tenure of Office Act (1867) sought to limit the president’s removal power, and Andrew Johnson’s defiance of that law led to his impeachment. Although Johnson was acquitted by a single vote, the episode revealed that the struggle between executive initiative and legislative oversight had become structural rather than situational.18 The presidency had emerged from the nineteenth century as both an institution of immense potential and one permanently entangled in the contradictions of democratic power.

The Progressive Era to the New Deal: Structural Transformation

The Progressive Presidency and the Seeds of Modern Executive Power

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the United States had become an industrial power whose social and economic problems dwarfed the capacity of nineteenth-century governance. The presidency, once reactive and restrained, now faced demands for active leadership. Progressive reformers, confronted with corruption, monopolies, and the inequities of industrial capitalism, reimagined government as an instrument of national purpose rather than limited arbitration. Within this climate, presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson reconceived the executive as the dynamic heart of reform.

Roosevelt, invoking a “stewardship theory” of the presidency, declared that a president could act on behalf of the people in any matter not explicitly forbidden by the Constitution.19 He used the office to confront corporate monopolies, mediate labor disputes, and expand conservation policy, all through vigorous use of executive orders and direct appeals to public opinion.20 His successor, William Howard Taft, objected to this expansive interpretation, arguing for strict adherence to constitutional text, but the cultural shift had already taken root.21 Wilson, meanwhile, transformed presidential communication. His regular addresses to Congress, public oratory, and wartime leadership during World War I fused moral persuasion with executive direction, marking a new stage in the presidency’s fusion of charisma and power.22

The Progressive presidency thus established new norms: national leadership through administration, legislation through persuasion, and executive accountability mediated by public approval. These developments did not rewrite the Constitution but redefined its practice. By 1920, the executive branch had become both the moral and managerial center of federal power, a transformation accelerated, though not completed, by the crises to come.

The New Deal and the Birth of the Administrative State

The Great Depression confronted the nation with collapse on a scale the framers could not have imagined. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal revolutionized the federal government’s structure and permanently altered the balance among its branches. Roosevelt did not merely expand the presidency’s authority; he institutionalized it. Through the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, and the creation of alphabet agencies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Civilian Conservation Corps, he embedded executive administration into the daily fabric of American life.23

The Supreme Court initially resisted, striking down several New Deal measures as unconstitutional delegations of legislative authority. Yet Roosevelt’s eventual victory in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. (1937) validated broad federal regulation and affirmed the president’s role as chief administrator of national recovery.24 The following year, the Reorganization Act of 1939 formalized the Executive Office of the President, consolidating the Bureau of the Budget and other agencies under direct White House control.25 This created a permanent administrative apparatus capable of coordinating policy across the expanding bureaucracy.

The New Deal also redefined the presidency as an emotional and symbolic office. Through radio “fireside chats,” Roosevelt forged a direct relationship with citizens, bypassing Congress and the press.26 His leadership style (personal, persuasive, performative) reshaped political expectations: Americans now looked to the president not only to govern but to comfort, inspire, and act decisively in crisis. The implications of this shift were profound. The executive branch, once limited to enforcing laws, had become the chief generator of them. By the close of World War II, the presidency was no longer a constitutional mechanism; it was the nation’s central political institution.

The Postwar, Cold War, and Modern Presidency (1945–2000)

National Security and the Rise of the Imperial Presidency

The end of World War II ushered in an era when the American presidency became synonymous with global power. The United States emerged as a superpower, facing a nuclear-armed Soviet Union and an ideological struggle that required constant vigilance. Under these conditions, the president’s constitutional role as commander-in-chief expanded beyond anything previously imaginable. The creation of the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency through the National Security Act of 1947 institutionalized a permanent security apparatus under executive direction.27 Harry S. Truman’s decision to deploy atomic weapons without prior congressional authorization in 1945 marked the arrival of unilateral executive control over the most destructive force in human history.28

Cold War presidents wielded military and covert authority with increasing autonomy. Truman’s intervention in Korea in 1950, justified as a “police action” under United Nations auspices, established a precedent for conducting major military operations without formal declarations of war.29 Dwight D. Eisenhower continued this pattern through covert operations orchestrated by the CIA, toppling governments in Iran and Guatemala in 1953 and 1954.30 The presidency during this period “had become the pivot of a national security state, ruling by secrecy, surveillance, and continuous crisis.”31

By the 1960s, the institutional momentum of the national security presidency was self-sustaining. John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson inherited a bureaucracy of global reach that fused military power, intelligence, and diplomacy under executive management. The Vietnam War deepened this transformation: decisions of escalation and strategy were increasingly centralized in the White House, while Congress, divided and deferential, failed to assert its constitutional prerogatives.32 The result was an executive branch that commanded the machinery of war abroad and the administrative apparatus of reform at home.

Domestic Consolidation and the Politics of Power

While foreign crises elevated presidential primacy, domestic politics solidified it. The growth of the administrative state during the postwar boom granted presidents extensive influence over economic regulation, civil rights enforcement, and social welfare programs. Franklin Roosevelt’s innovations had created the architecture; his successors learned how to operate it. John F. Kennedy’s “New Frontier” and Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” relied on executive coordination across dozens of agencies to enact sweeping social legislation.33

Yet as the presidency expanded, so too did public skepticism. The Watergate scandal (1972–74) revealed the dark underside of unchecked executive authority: secrecy, surveillance, and abuse of power. Richard Nixon’s assertion of “executive privilege” to withhold information from Congress provoked a constitutional crisis that culminated in his resignation.34 In response, Congress enacted reforms, the War Powers Resolution (1973), the Budget and Impoundment Control Act (1974), and the creation of intelligence oversight committees, to restore legislative checks.35 Though these efforts curbed the most flagrant abuses, they did not reverse the underlying trend. Each new national emergency revived the impulse toward executive control.

The late twentieth century produced presidents who mastered the politics of symbolic leadership. Ronald Reagan, a former actor, used television to communicate directly with the public, framing policy through narrative and emotion rather than bureaucracy.36 Bill Clinton later perfected this performative model, governing through triangulation and rapid-response communication while presiding over an increasingly complex administrative machine.37 By the end of the century, the presidency had evolved into both a managerial superstructure and a permanent campaign, an institution that governed and persuaded simultaneously.

The Cold War’s conclusion in 1991 offered no respite. Instead, it left a vacuum in which executive power, justified by decades of existential struggle, had become habitual. The structure of national security, the culture of presidential immediacy, and the expectation of decisive leadership remained firmly embedded in American political life.38

The Post-9/11 Era to the Present: Acceleration and Challenge

National Security and the Crisis Presidency

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, marked a decisive rupture in the balance between liberty and security, catapulting the presidency into an era of permanent emergency. Congress’s Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) of 2001 empowered President George W. Bush “to use all necessary and appropriate force” against those responsible for the attacks. In practice, this vague mandate became a blank check for a global campaign unconstrained by geographic or temporal limits.39 The Bush administration claimed sweeping powers of surveillance, detention, and targeted killing, justified under a theory of the “unitary executive” that placed wartime discretion almost entirely within the president’s hands.40

Legal scholars and journalists chronicled the extraordinary elasticity of this doctrine. Secret memoranda from the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel, later revealed by congressional investigations, argued that the president could override statutes and treaties in the name of national defense.41 The establishment of the detention camp at Guantánamo Bay and the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” extended executive control into moral territory once thought off-limits. While the Supreme Court reasserted judicial limits in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006) and Boumediene v. Bush (2008), these decisions curbed practice only at the margins.42 What emerged was a presidency operating through secrecy and technology, exercising lethal authority far from the traditional battlefield.

Continuity and Expansion Across Administrations

The Obama administration initially pledged restraint but institutionalized much of its predecessor’s security architecture. Targeted drone strikes expanded dramatically, conducted under classified presidential findings and without formal congressional authorization.43 At the same time, President Barack Obama’s reliance on executive orders and regulatory action in domestic policy (covering immigration, climate change, and healthcare) signaled that unilateral governance had become bipartisan habit rather than partisan excess.44

Subsequent administrations pushed this trend into overt confrontation. President Donald Trump invoked emergency powers to reallocate defense funds for his border wall after Congress refused appropriations, illustrating how “emergency” had become a political tool rather than an exceptional measure.45 He also claimed near-total immunity from criminal investigation while in office, a position rebuked by the Supreme Court in Trump v. Vance (2020).46 Yet even judicial reversals failed to dent the cultural expectation that the president acts first and answers later. The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced this reality, as the public demanded federal solutions that only the executive branch could deliver swiftly.

By the mid-2020s, the cumulative effect of crisis, partisanship, and media saturation had produced what scholars call the “permanent emergency presidency.”47 The same technologies that empower presidents to speak directly to citizens also allow them to bypass institutional mediation. Information warfare, social media, and instantaneous communication have fused leadership and spectacle. Presidents now govern in real time, their authority measured less by legal restraint than by narrative dominance.

Democracy and the Future of Executive Power

The modern presidency’s reach has prompted renewed debate about constitutional design. Critics argue that Congress, paralyzed by polarization, has effectively delegated its powers, creating what one analyst termed “a vacuum filled by energy rather than law.”48 Supporters counter that global complexity demands decisive leadership, and that a strong executive remains the only institution capable of coherent action in crisis. Both claims hold truth. The presidency’s growth reflects not only ambition but also necessity, an adaptive response to the demands of an interconnected world.

Still, the danger persists that emergency will become routine and discretion indistinguishable from authority. Efforts to recalibrate include proposals for statutory limits on emergency declarations, enhanced transparency for drone operations, and congressional reassertion of war-powers oversight. Whether such measures can succeed depends less on constitutional text than on civic will. As historian William Howell observes, “Institutions follow incentives, and presidents rarely surrender the tools their predecessors have built.”49 The challenge for twenty-first-century America is thus not simply to restrain executive power, but to reconstruct the habits of shared governance that once gave it meaning.

Mechanisms of Growth and Theoretical Reflections

Structural Mechanisms Behind Expansion

The growth of executive power across American history cannot be explained merely by personality or politics; it is institutional, embedded in the structure of modern governance. The Constitution’s deliberate silences, particularly the “vesting” and “take care” clauses of Article II, invite interpretation. Every assertion of presidential authority that went unchallenged, or that survived challenge, became a precedent for future expansion.50 Over time, necessity turned into norm.

War and national emergency have been the most reliable accelerants. Each conflict from the Civil War to the “war on terror” generated exceptional powers later normalized in peacetime.51 The Cold War’s perpetual threat institutionalized emergency itself, embedding secrecy, surveillance, and military readiness into daily governance. Administrative growth compounded this dynamic. As the federal bureaucracy expanded to manage an industrial and later global economy, the president emerged as the only figure capable of coordinating its vast machinery.52 Delegation from Congress, justified as efficiency, effectively concentrated discretion in the executive branch.

Equally decisive have been changes in media and political culture. The presidency’s voice, amplified from radio to television to social media, has become a direct conduit to the public. Theodore Roosevelt’s “bully pulpit” evolved into Franklin Roosevelt’s “fireside chats,” John F. Kennedy’s televised charisma, and the digital immediacy of twenty-first-century presidents.53 Public expectation now defines authority: citizens demand that presidents act swiftly, personally, and visibly, while Congress deliberates slowly. The structural advantage thus lies with action rather than restraint—a psychological as well as institutional asymmetry that the framers could not have foreseen.

The Balance of Powers in a Changing Republic

The steady aggrandizement of executive power has prompted recurring efforts to restore equilibrium. After Watergate, Congress reasserted oversight through legislation and investigative committees, yet each subsequent crisis has eroded those gains. Scholars such as Louis Fisher and Bruce Ackerman have argued that genuine reform requires not new statutes but a renewed political culture of accountability.54 The courts, though occasionally assertive, have generally avoided direct confrontation, preferring doctrines—like the “political question” principle—that defer to the executive in matters of war and diplomacy.55

Still, the constitutional system endures. The same framework that allowed expansion also enables correction. The presidency’s power grows through consent as much as assertion: Congress funds the bureaucracy, the courts validate new doctrines, and the public rewards decisive leadership. The endurance of the republic thus depends not solely on law but on civic memory, the collective willingness to remember that strength without balance is not stability but decay.

Conclusion

From Washington’s modest oath to the twenty-first-century “imperial presidency,” the trajectory of American executive power traces the history of the republic itself, its fears, ambitions, and evolving sense of governance. Each era has redefined what the presidency means. In the founding generation, it was a restrained executor of law. In the nineteenth century, it became a symbol of national unity. The twentieth century transformed it into a managerial and military institution, and the twenty-first has made it the focal point of global and digital authority.

The growth of executive power is neither aberration nor accident. It reflects structural necessity in a world where crises are constant and complexity vast. Yet necessity can obscure danger. A presidency that acts without limit risks consuming the very checks that legitimate it. The framers’ genius lay not in perfect foresight but in designing a system flexible enough to absorb change while preserving liberty. That flexibility now faces its greatest test. Whether future generations restore equilibrium or embrace permanent presidential governance will determine not merely the fate of an office, but the character of the American republic itself.

Appendix

Footnotes

- William P. Marshall, “Eleven Reasons Why Presidential Power Continually Expands,” Boston University Law Review 85, no. 2 (2005): 423–45.

- “Presidency of the United States of America – Historical Development,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed October 2025.

- Reorganization Act of 1939, Pub. L. No. 76-19, 53 Stat. 561.

- Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., The Imperial Presidency (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973).

- Brennan Center for Justice, “Executive Power,” accessed October 2025, https://www.brennancenter.org.

- Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), 268–75.

- Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 70, in The Federalist Papers, ed. Clinton Rossiter (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), 423.

- Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Vintage, 2004), 192–210.

- Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 193–205.

- Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (New York: Random House, 2012), 311–15.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 48–61.

- Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power, 3rd ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013), 19–25.

- Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 87–91.

- John C. Calhoun, Speeches of John C. Calhoun (New York: D. Appleton, 1843), 211–13.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 392–401.

- James M. McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (New York: Penguin, 2008), 44–55.

- Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 330–35.

- Theodore Roosevelt, An Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1913), 388–92.

- Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex (New York: Random House, 2001), 64–77.

- William Howard Taft, Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers (New York: Columbia University Press, 1916), 21–27.

- John Milton Cooper Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 311–18.

- William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932–1940 (New York: Harper & Row, 1963), 47–56.

- NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1 (1937).

- Reorganization Act of 1939, Pub. L. No. 76-19, 53 Stat. 561.

- Robert Dallek, Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 89–92.

- National Security Act of 1947, Pub. L. No. 80-253, 61 Stat. 495.

- Garry Wills, Bomb Power: The Modern Presidency and the National Security State (New York: Penguin, 2010), 25–33.

- Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power, 3rd ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013), 97–103.

- Stephen Kinzer, Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq (New York: Times Books, 2006), 117–29.

- Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., The Imperial Presidency (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973), 134.

- Fredrik Logevall, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 78–85.

- Robert Dallek, Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 241–53.

- Stanley I. Kutler, The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon (New York: W.W. Norton, 1990), 587–601.

- Philip B. Kurland, Watergate and the Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 45–58.

- Gil Troy, Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 101–12.

- Michael Nelson, ed., The Presidency and the Political System, 12th ed. (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2020), 413–20.

- Andrew Rudalevige, The New Imperial Presidency: Renewing Presidential Power after Watergate (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005), 203–10.

- Authorization for Use of Military Force, Pub. L. No. 107-40, 115 Stat. 224 (2001).

- John C. Yoo, The Powers of War and Peace: The Constitution and Foreign Affairs after 9/11 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 58–64.

- Charlie Savage, Power Wars: Inside Obama’s Post-9/11 Presidency and the National Security State (New York: Little, Brown, 2015), 42–49.

- Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557 (2006); Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008).

- Micah Zenko, Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2013), 9–12.

- Kenneth R. Mayer, With the Stroke of a Pen: Executive Orders and Presidential Power (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 205–12.

- Cristina M. Rodríguez and Adam B. Cox, “The President and Immigration Law Redux,” Yale Law Journal 125, no. 1 (2015): 104–09.

- Trump v. Vance, 591 U.S. ___ (2020).

- Elizabeth Goitein, “The Alarming Scope of the President’s Emergency Powers,” The Atlantic, January 2019.

- Neil Kinkopf, “Inherent Presidential Power and Constitutional Structure,” Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 1 (2007): 37-48.

- William G. Howell, Power without Persuasion: The Politics of Direct Presidential Action (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 229.

- Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash, Imperial from the Beginning: The Constitution of the Original Executive (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 15–21.

- Bruce Ackerman, The Decline and Fall of the American Republic (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 47–53.

- James P. Pfiffner, The Modern Presidency (Boston: Cengage Learning, 1994), 88–92.

- Jeffrey Tulis, The Rhetorical Presidency (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 13–19.

- Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power, 3rd ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013), 254–59.

- Alexander M. Bickel, The Least Dangerous Branch: The Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 126–29.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Bruce. The Decline and Fall of the American Republic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Authorization for Use of Military Force, Pub. L. No. 107-40, 115 Stat. 224 (2001).

- Bickel, Alexander M. The Least Dangerous Branch: The Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

- Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008).

- Brennan Center for Justice. “Fighting Abuse of Executive Power.” Accessed October 2025.

- Calhoun, John C. Speeches of John C. Calhoun. New York: D. Appleton, 1843.

- Cooper, John Milton Jr. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

- Dallek, Robert. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

- ———. Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. New York: Vintage, 2004.

- Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- Fisher, Louis. Presidential War Power. 3rd ed. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Goitein, Elizabeth. “The Alarming Scope of the President’s Emergency Powers.” The Atlantic, January 2019.

- Greenberg, Amy S. A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

- Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557 (2006).

- Hamilton, Alexander. Federalist No. 70. In The Federalist Papers, edited by Clinton Rossiter, 423. New York: Signet Classics, 2003.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Howell, William G. Power without Persuasion: The Politics of Direct Presidential Action. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Kinkopf, Neil. “Inherent Presidential Power and Constitutional Structure.” Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 1 (2007): 37-48.

- Kinzer, Stephen. Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq. New York: Times Books, 2006.

- Kurland, Philip B. Watergate and the Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

- Kutler, Stanley I. The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon. New York: W.W. Norton, 1990.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932–1940. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

- Logevall, Fredrik. Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Marshall, William P. “Eleven Reasons Why Presidential Power Continually Expands.” Boston University Law Review 85, no. 2 (2005): 423–45.

- Mayer, Kenneth R. With the Stroke of a Pen: Executive Orders and Presidential Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- McPherson, James M. Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief. New York: Penguin, 2008.

- Meacham, Jon. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. New York: Random House, 2012.

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. New York: Random House, 2001.

- National Security Act of 1947, Pub. L. No. 80-253, 61 Stat. 495.

- Nelson, Michael, ed. The Presidency and the Political System. 12th ed. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2020.

- NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1 (1937).

- Pfiffner, James P. The Modern Presidency. Boston: Cengage Learning, 1994.

- Prakash, Saikrishna Bangalore. Imperial from the Beginning: The Constitution of the Original Executive. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

- Rakove, Jack N. Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York: Knopf, 1996.

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845. New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

- Reorganization Act of 1939, Pub. L. No. 76-19, 53 Stat. 561.

- Rodríguez, Cristina M., and Adam B. Cox. “The President and Immigration Law Redux.” Yale Law Journal 125, no. 1 (2015): 104–09.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. An Autobiography. New York: Macmillan, 1913.

- Rudalevige, Andrew. The New Imperial Presidency: Renewing Presidential Power after Watergate. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

- Savage, Charlie. Power Wars: Inside Obama’s Post-9/11 Presidency and the National Security State. New York: Little, Brown, 2015.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. The Imperial Presidency. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973.

- Taft, William Howard. Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916.

- Troy, Gil. Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Trump v. Vance, 591 U.S. ___ (2020).

- Tulis, Jeffrey. The Rhetorical Presidency. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Wills, Garry. Bomb Power: The Modern Presidency and the National Security State. New York: Penguin, 2010.

- Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Yoo, John C. The Powers of War and Peace: The Constitution and Foreign Affairs after 9/11. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Zenko, Micah. Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2013.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.